Gurgaon DLF phase 3 has a giant illegal guest-house problem. Over 4,000 notices, yet business as usual

Gurugram: Rajesh Singh operates three guest-houses in Gurugram’s DLF Phase-3 and each caters to a different demographic. There’s one for couples looking for a quick getaway, another for corporate staffers, and a third targeted at medical tourists. Except it’s all illegal.

Gurugram has a massive illegal guest-house problem. And the authorities have been on a notice-raid-rinse-repeat cycle for decades. But Phoenix-like, the illegal constructions keep rising. In January, notices were slapped on over 4,000 such properties in DLF City, encompassing the city’s most prime and plush neighbourhoods. Then in February, acting on petitions filed in 2021 by residents’ welfare organisations, the Punjab & Haryana High Court ordered the state government to clamp down on these illegal dwellings and commercial establishments in residential areas within two months.

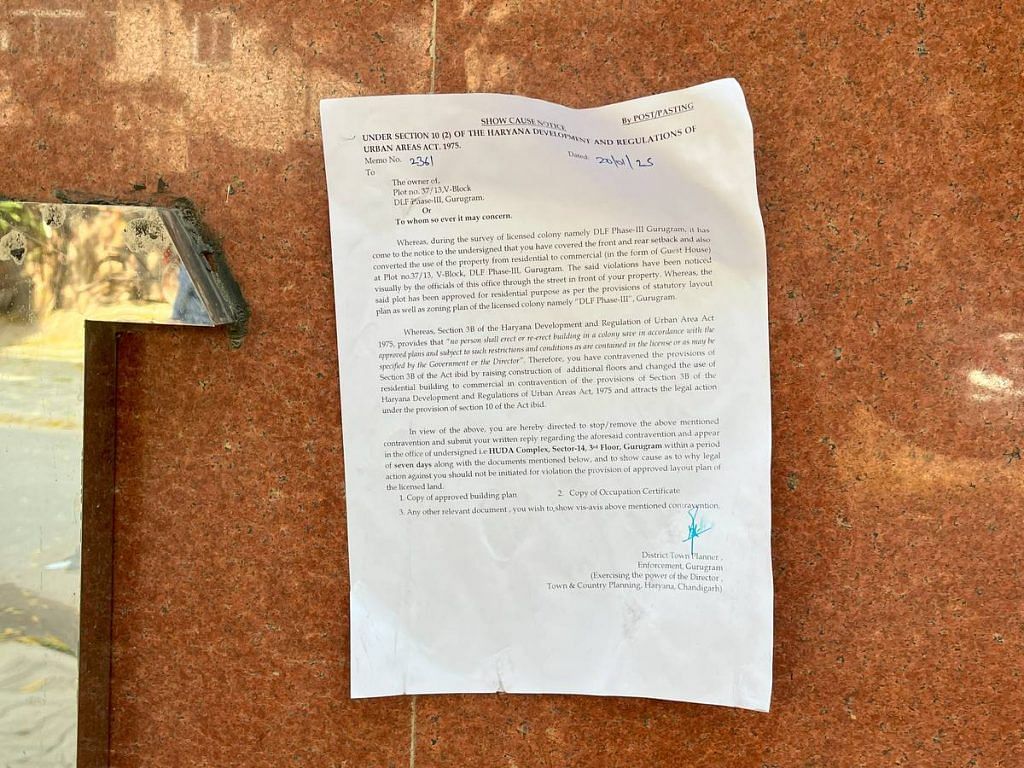

The latest notices are ultimatums, not just warnings. Singh, who received his first-ever notice last month, along with many others, has been ordered to bring commercial operations to a complete and unambiguous halt by seven days—or else. While notices have been issued time and again, officials insist this time is different. They’re promising an irreversible crackdown—legal consequences, sealing, and, as a final measure, demolition.

Gurugram began as a mini city of giant malls. Today, many of them are ghost malls. But illegal guest houses, beauty parlours, laser hair removal centres, and hotels are flourishing and cramming residential neighbourhoods.

Singh’s three establishments sit on residential land he has leased, and the government’s stern showcause notice applies to them all. But he is nonchalant.

“Look at the scale of the boom. Something or the other has to be illegal,” said Singh, reclining on an armchair in one of his 3-star guest-houses. “This is not my personal building. If they [the administration] tell me not to run it—I won’t.” But for now, he is.

Singh’s business chain is a microcosm of the so-called Millennium City, where land has become currency, capital, and power. His guest-houses are part of an explosion of unchecked commercialisation, with the detritus scattered across the city— glossy yet soulless glass-and-wood mid-range hotels masquerading as homes. Authorities are playing an endless game of whack-a-mole, trying to contain what they see as a blot in the gleaming promise of the Millennium City.

“Unauthorised construction has always been a problem. When development happens, such issues will arise. The solution is with the High Court. The DTP (District Town Planner) has always taken action by way of notices, sealing, and demolitions. It’s a long, ongoing process. We keep making the effort,” said Manish Yadav, former town planner.

You can’t walk. There’s rampant construction, and by and large, everyone is involved. You can’t touch builders, and you can’t touch the theka-walas (booze shops). There’s haphazard parking, violations of the floor area ratio. And this is a seismic zone. It’s a death trap

-Sanjay Lal, Gurugram resident

Between 2010 and 2024, the Department of Town and Country Planning reportedlyconducted 44 demolition and sealing drives in DLF city. Yadav, however, refused to provide numbers on how many notices and crackdowns have actually led to permanent shutdowns.

He also referred to this propensity for the illegal as “natural” in Gurugram.

These businesses didn’t appear overnight. Singh received the lease for his first guest-house in 2015—a decade ago. The problem has been creeping into neighbourhoods for years.

“It’s not like the department hasn’t been working. We’ve been tackling the same issues for the past 15, 20 years,” said Gurugram District Town Planner Amit Madholia. “People here don’t want to abide by the law.”

The owners of these illegal properties often take their cases to local courts, where the disputes drag on indefinitely. But this time, the High Court has prevented local courts from intervening.

These hotels exist across the spectrum. Some boast five-star lobbies with cafes and juice bars. Others are bare-bones and utilitarian—empty usually, except for a bleary-eyed supervisor monitoring the CCTV feed.

The illegal encroachments problem isn’t just an official headache. Neighbours are complaining too. The majority, according to local residents, cropped up following the Covid-19 pandemic.

Fifteen years ago, these were quiet, unremarkable streets lined with bungalows. Now, residents say their neighbourhoods have gone from calm to chaotic, clogged with illegally parked cars, garbage piling up, and a constant stream of strangers coming and going.

“We get complaints from their neighbours regularly. But 98-99 per cent of these places are already on our radar,” said Madholia. “These are highly rated residential areas. Why would people want this kind of nuisance?”

The neighbourhoods hit hardest by commercial encroachment are inhabited primarily by Gurugram’s self-professed crème de la crème. That’s why they can’t quite believe it’s happening to them.

Luxury homes, no parking space

The exodus to Gurugram began quietly, a migration fuelled by the high costs and space constraints of living in the capital. It offered vast tracts of land, cheaper housing, and fewer people. But soon, it became what it was meant to escape.

In 2017, the Haryana government amended its housing policy to accommodate the growing demand for housing, allowing residential buildings to go up to four floors, with an additional stilt floor designated for parking. However, concerns over infrastructure strain led to a temporary suspension of approvals in 2023, before they were reinstated in mid-2024 for some sectors. Last year, this led to protests in several parts of the city over the burden on infrastructure, with some RWAs even threatening to boycott elections.

As the city expands and space contracts, every inch is being used. Stilt parking is often converted into lobbies, adding to the woes of already exhausted residents. There’s already no space for their cars, and now they have to contend with those of weekend travellers.

It’s Gurugram’s wicked problem where everyone is entangled in inextricable ways.

“You can’t walk. There’s rampant construction, and by and large, everyone is involved. You can’t touch builders, and you can’t touch the theka-walas (booze shops). There’s haphazard parking, violations of the floor area ratio. And this is a seismic zone,” said Sanjay Lal, a Gurugram resident who contested the 2024 Haryana elections as an independent. “It’s a death trap.”

Buildings in DLF Phases 1, 2, and 3 are packed so tightly together that it’s difficult to discern where one ends and the next begins As a result, they’re in violation of fire safety norms, which, per building bye-laws, demand a fixed number of exits and ample exterior space. What frustrates residents most is that they’ve watched it all unfold, while being completely powerless to stop it.

“This is not something that’s happened underground. It’s been right in front of our eyes and under our noses,” said Ritu Bhariok, a resident of DLF Phase 5 and an RWA member. “Every area has an official. What were they doing? Were they sleeping?”

The neighbourhoods hit hardest by commercial encroachment are inhabited primarily by Gurugram’s self-professed crème de la crème. That’s why they can’t quite believe it’s happening to them.

“Not one complaint by the RWA has gone through,” said Bhariok.

What is truly mind-boggling is that under the glassy, glitzy façade of Gurugram lies a massive EWS scam—an affordable housing policy set in place for the poor.

Shape-shifting buildings and an EWS ‘scam’

There’s a building in Gurugram’s DLF Phase 4 that’s in a constant state of transformation. The ground floor is currently a BMW showroom, while the first floor hosts an upscale cafe. Before that, it was Punjab Grill, a Mughlai restaurant. At another point, it was Mocha, a cafe-cum-sheesha bar.

This piece of land belongs to a farmer from Chakkarpur, an urban village nearby. Originally, he received permission to use it for a flour mill. But he’s expanded far beyond—illegally. It’s arguably a testament to resilience, reinvention, and, as far as the authorities are concerned, indifference.

A few kilometres away in DLF Phase 3, similar cases abound. In one building, there’s a Barista where stilt parking was supposed to be. In another, the RITES Limited guest-house has an peeling A4 sheet pasted outside. Dated 20 January, it instructs the owner to “stop/remove the above mentioned contravention” of converting a residential property into a commercial one.

This guest house belongs to a railway infrastructure company under the Railway Ministry, and is reserved for their staff.

“We’ve had no difficulty since the notice was issued,” shrugged Prayatana, the guest-house manager.

He isn’t sure if the company or landowner has responded to the show-cause notice. But operations continue just as they have for the past two years. Prayatana, who works for Nimbus Harbor, a property management company, joked that this was a case of the government issuing a notice against itself, since RITES Ltd belongs to the Railway Ministry.

In DLF Phase 3 alone, approximately 700 show-cause notices were issued in January. Yet business carries on. At Hari’s Court, a business hotel-cum-banquet hall that opened eight months ago, manager Karmchand Bhardwaj claims he has informed the landowner about the notice. But all 35 rooms are available for booking.

Of course, this [the illegality] is an issue. But look at the kinds of porches and servants’ quarters residents have built

-Rajesh Singh, owner of 3 guest-houses

What is truly mind-boggling is that under the glassy, glitzy façade of Gurugram lies a massive EWS scam—an affordable housing policy set in place for the poor.

Of the illegal properties that have come under the authorities’ scanner, 83 per cent belong to the EWS (economically weaker section) category. But according to Madholia, these businesses are largely operated by the wealthy. Over the past 15–20 years, the wealthy have almost completely taken over EWS housing.

“It’s EWS housing that’s seen the maximum modifications. Homes in Nathupur [an urban village in DLF Phase 3] go up to five or six floors,” said Bhariok.

According to the district administration, residential areas allow up to 25 per cent commercial use under a no-nuisance clause. Essentially, one room or one floor can be converted for a commercial enterprise, such as a doctor seeing patients from home.

But in DLF Phase 3, the commercial has now overtaken the residential. Narrow lanes are inundated with waste and the exasperated sighs of residents. However, some businesses insist that they are not illegal.

SaltStayz, a boutique chain of mid-range hotels, sits on a street overrun by construction. But since it’s on a relatively wide lane that has always been commercially heavy, it isn’t much of a hindrance to the area’s residents. Still, despite the manager claiming that their operations are legal, they too have received a notice.

Red tape and grey zones

Seated in his guest-house in Phase 3, Singh draws comfort from the tiny grey zone that runs between departments and jurisdictions, legal and illegal, fine print and red tape, harassment and compliance. He whips out the permissions he’s received over the years, which he admits were acquired “under the table”. He points to a note from the Municipal Corporation of Gurgaon that allows him to run his guest-house.

However, the distinction between residential and commercial land is sacrosanct. The land-use agreement cannot be changed, said Madholia.

Unfazed as he is, Singh insists that he operates like any legitimate business. His water and electricity bills are charged at commercial rates. He has CCTV cameras, he’s conducted staff verifications, and he takes pains to ensure that his neighbours’ fears are assuaged. He doesn’t allow unmarried couples in his V Block property.

“I run a corporate business. You can find me on MakeMyTrip. And now this is a commercial hub,” he said. “Of course, this [the illegality] is an issue. But look at the kinds of porches and servants’ quarters residents have built.”

With the threat of closure looming, Singh is preparing a hasty exit from Gurugram, planning to return to his home state of Uttarakhand. His next plan is to shift into another thriving industry—travel.

Meanwhile, a tired and frustrated Madholia is firm.

“This time, if the property owners don’t respond—I will personally demolish and seal these businesses,” he declared.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

News Sources :- https://theprint.in/